|

Magic Realism has emerged as one of the more intriguing art terms

over the past few decades. Often misunderstood and seldom embraced

by critics and artists without reservations, Magic Realism occupies an important niche in

art history, one which warrants more scholarly investigation and

rigorous elucidation. A thorough survey of German art during the

Weimar era, along with fresh assessments of the impact of Naive art, Metaphysical

art and Surrealism on European and American

artists during the four decades that followed World War I, are important

exercises in developing a full understanding of Magic Realism. Also

it is important to recognize that both style and

content together create the "magic" in a Magic Realism

painting, especially in works by the American Magic Realists of the

1940s and 50s.

Many discussions about Magic Realism begin with historical

references to the German writer Dr. Franz Roh and cite German art

during the years of the Weimar Republic as the source of this type

of art. However, Weimar art was diverse and an extensive review of

this period is needed to appreciate the complex dynamics that

influenced German artists during the years following World War I.

Many artists in fact transitioned between styles, adapting their

approach as the social, political and economic environments changed.

Traits of Magic Realism can be identified in many works of art

painted in Germany during this era, but it is difficult to establish

that a cohesive movement evolved. It is more accurate to describe

Weimar art as a melting pot of styles which produced a broad range

of Magic Realism paintings and which in turn was connected to a

broader movement outside Germany.

| This article has

been registered with the United States Copyright Office. |

Franz Roh coined the term Magic Realism in

Nach-expressionsmus, magisher Realismus, Probleme der neuesten

europaischer Malerei

1a, published in 1925. In his book Roh

carefully detailed the stylistic

characteristics of a new

art

movement which he called Post-Expressionism, and contrasted them

with Expressionism. He gave this new type of art the byname Magic

Realism, in order to suggest what he considered its special

evocative qualities.

In June 1925, Gustav Hartlaub opened an exhibition Die Neue

Sachlichkeit in Mannheim.

Roh and Hartlaub seemed to

focus on similar art when first commenting on Post-Expressionism,

art which was moving away from abstraction and emotionally charged

imagery. Hartlaub initially emphasized that he saw a division of two

separate wings within this type of art, a classically oriented right

wing and a socially critical left one

1b. Roh helped him to organize

the exhibition, but he avoided supporting Hartlaub's bipolar

outlook. Roh felt instead that there was a singular movement away

from Expressionism, which had many manifestations and which was also

evident in other European countries. art

movement which he called Post-Expressionism, and contrasted them

with Expressionism. He gave this new type of art the byname Magic

Realism, in order to suggest what he considered its special

evocative qualities.

In June 1925, Gustav Hartlaub opened an exhibition Die Neue

Sachlichkeit in Mannheim.

Roh and Hartlaub seemed to

focus on similar art when first commenting on Post-Expressionism,

art which was moving away from abstraction and emotionally charged

imagery. Hartlaub initially emphasized that he saw a division of two

separate wings within this type of art, a classically oriented right

wing and a socially critical left one

1b. Roh helped him to organize

the exhibition, but he avoided supporting Hartlaub's bipolar

outlook. Roh felt instead that there was a singular movement away

from Expressionism, which had many manifestations and which was also

evident in other European countries.

Hartlaub first tried to

organize his exhibition in 1923, however hyperinflation made that

impossible. He finally succeeded in 1925. In the catalog he

emphasized that the exhibition was not opposed to Expressionism, but

that it was presenting a new type of art that was emerging in

Germany. Artworks by Verist (socially critical) artists like Otto

Dix and George Grosz were included, but Hartlaub took great pains

not to include controversial or provocative works, hoping to avoid any

negative repercussions. The exhibition received strong support from

the press and it made a profound impression on the public.

Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) became a

label applied by many writers when referring to the typical

representational styles that developed during Weimar period. Within

a short time after the exhibition many German artists adopted a

cool, detached, matter-of-fact style, which was particularly evident in portraits.

This

style became palatable to bourgeois tastes, and the

last vestiges of Expressionism were shed. Unfortunately, the National

Socialists took control of Germany in 1933, and the Weimar era

ended. The Nazis installed an official state approved style, das

Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil). Within a few years many works by

the prominent artists of Neue Sachlichkeit were branded as

Degenerate Art. Many paintings were confiscated; some were publically burned. Post-Expressionism by any name came to an

end. Roh's term Magic Realism was never widely used in Germany during the

Weimar era, but his concepts were well known in artistic circles and

spread within Europe and eventually to the Americas.

A review of Hautlaub's Die Neue Sachlichkeit exhibition catalog

reveals that almost half of paintings presented were produced by

either Max Beckmann or by painters associated

with Munich (Schrimpf,

Kanoldt, Mense,

Erbsloeh,

Schulz-Matan and

Daveringhausen). Franz Roh lived

near Munich and followed developments there closely. Many historians

subsequently identified the Munich artists as central to Roh's Magic

Realism. Most of these artists dispersed by 1926, and Munich lost

its role as the most important center of Post-Expressionism. With

regard to Max Beckmann, Hartlaub considered him to be the leader of the

new movement. However, by 1925 Beckmann had shifted away from his

Magic Realist phase, and moved toward a more individualistic style,

one ultimately integrated diverse influences, including

Cezanne, Grünewald,

Brueghel and medieval stained glass.

Max Beckmann or by painters associated

with Munich (Schrimpf,

Kanoldt, Mense,

Erbsloeh,

Schulz-Matan and

Daveringhausen). Franz Roh lived

near Munich and followed developments there closely. Many historians

subsequently identified the Munich artists as central to Roh's Magic

Realism. Most of these artists dispersed by 1926, and Munich lost

its role as the most important center of Post-Expressionism. With

regard to Max Beckmann, Hartlaub considered him to be the leader of the

new movement. However, by 1925 Beckmann had shifted away from his

Magic Realist phase, and moved toward a more individualistic style,

one ultimately integrated diverse influences, including

Cezanne, Grünewald,

Brueghel and medieval stained glass.

Franz Roh stated that Magic Realism should not simply bring back

"the more neutral art of Courbet and Leibl"

1c. He opposed any revival

of 19th Century academic art, feeling that artists should avoid

regression.

Kanoldt,

Schrimpf and Mense of

the

Munich group all had connections

with Italian art through various

Deutsch-Römer

19th Century artists, but they were also heavily influenced by a

number of

Italian contemporary artists, particularly

Carlo Carra and

Giorgio de Chirico. A number of important German

artists outside Munich were influenced by de Chirico's art,

including Anton Raederschidt, George Grosz,

Rudolf Dischinger,

Felix Nussbaum and Max Ernst. The

paintings of

Henri Rousseau, the French primitivist, had an even

broader influence on Weimar art.

Naive nuances are often apparent in the works of many

German artists, including those by Max

Beckmann, Carl Grossberg,

Georg Scholz,

Wilhelm Schnarrenberger,

Ernst Thoms,

Niklaus Stoeklin,

Grethe Jüergens,

Erich Wegner,

Walter Spies,

Niklaus Stoeklin, Gyorgy Stefula and

Adolf Dietrich.

In his 1957 book, L'Art magique, Andre Breton wrote "with

Rousseau we can for the first time talk about Magic Realism"

1d.

The postwar period saw the spread of a counter-Modernist

movement in the arts, known as the Return to Order (or Call to O rder),

which included the revival of many traditional painting techniques.

In Italy Il

Novecento Italiano in

particular stood out in this regard, through the paintings of

Felice Casorati,

Achille Funi, Ubaldo Oppi,

Gino Severini and

Antonio Donghi., as did works by

Andre Derain,

Felix Vallotton and

Auguste Herbin in France.

Around 1925 a strong tendency toward precision and

illusionism emerged within German art. This was partially due to

the success of Hautlaub's exhibition but the trend was also

supported by a steady influx of new artists. Many artists

became interested in the art of the early Renaissance and adopted techniques

based on their careful studies of the Flemish and German Masters. By

the mid 1920s numerous intensely detailed paintings began to appear,

sometimes exhibiting an almost unnatural realism. Often the "magic"

of these paintings was embedded in the details of the work, by

juxtaposition or isolation of objects, or by an unusual perspective.

Important variations of Magic Realism developed from this tendency.

The paintings of

Franz Radziwill are good examples, as he often instilled an

eerie atmosphere into his works by an unusual color palette.

Equally notable were

architectonic paintings of Carl Grossberg,

who sometimes added uncanny elements to his works such as bats,

birds or apes. The portraits of Otto Dix manifested a versatility in

capturing "types" of German people of the 1920s. Meanwhile

Christian Schad studied Raphael and other Italian Masters while

living in Naples during the early 1920s. Schad's paintings consistently exhibited a cool

and almost photographic sharpness, but he often included both naive

and metaphorical elements. His paintings

are often cited by art historians as the quintessential art of Neue

Sachlichkeit. Many of Schad's paintings also exhibit unusual and

intangible qualities connecting him to Magic Realism, particularly

during his stays in Naples and Vienna, and after World War II. rder),

which included the revival of many traditional painting techniques.

In Italy Il

Novecento Italiano in

particular stood out in this regard, through the paintings of

Felice Casorati,

Achille Funi, Ubaldo Oppi,

Gino Severini and

Antonio Donghi., as did works by

Andre Derain,

Felix Vallotton and

Auguste Herbin in France.

Around 1925 a strong tendency toward precision and

illusionism emerged within German art. This was partially due to

the success of Hautlaub's exhibition but the trend was also

supported by a steady influx of new artists. Many artists

became interested in the art of the early Renaissance and adopted techniques

based on their careful studies of the Flemish and German Masters. By

the mid 1920s numerous intensely detailed paintings began to appear,

sometimes exhibiting an almost unnatural realism. Often the "magic"

of these paintings was embedded in the details of the work, by

juxtaposition or isolation of objects, or by an unusual perspective.

Important variations of Magic Realism developed from this tendency.

The paintings of

Franz Radziwill are good examples, as he often instilled an

eerie atmosphere into his works by an unusual color palette.

Equally notable were

architectonic paintings of Carl Grossberg,

who sometimes added uncanny elements to his works such as bats,

birds or apes. The portraits of Otto Dix manifested a versatility in

capturing "types" of German people of the 1920s. Meanwhile

Christian Schad studied Raphael and other Italian Masters while

living in Naples during the early 1920s. Schad's paintings consistently exhibited a cool

and almost photographic sharpness, but he often included both naive

and metaphorical elements. His paintings

are often cited by art historians as the quintessential art of Neue

Sachlichkeit. Many of Schad's paintings also exhibit unusual and

intangible qualities connecting him to Magic Realism, particularly

during his stays in Naples and Vienna, and after World War II.

An important characteristic of Magic Realism is ultrasharp

focus. Sharp detail is seen throughout many painting, including in

the background. Highly defined and even exaggerated detail may also

appear selectively in areas that the artist wishes to accentuate.

The overall effect is to move the viewer's attention all over the

painting,

,%201928%201b.jpg) before the totality of the composition can be comprehended. This

same effect frequently occurs in naive paintings

and also occurred in many works by the German and Flemish

Renaissance Masters. Another characteristic often seen in Magic

Realism paintings is an almost unnatural clarity. In many cases this

stemmed from a flattened tonality and/or idealized lighting, or from

suppression and/or selective use of shadows. As a result of these

factors, many Magic Realism paintings exhibit a false naturalism. before the totality of the composition can be comprehended. This

same effect frequently occurs in naive paintings

and also occurred in many works by the German and Flemish

Renaissance Masters. Another characteristic often seen in Magic

Realism paintings is an almost unnatural clarity. In many cases this

stemmed from a flattened tonality and/or idealized lighting, or from

suppression and/or selective use of shadows. As a result of these

factors, many Magic Realism paintings exhibit a false naturalism.

A focus on objects helped to define the works of German artists

during the Weimar years. Franz Roh stated that Magic Realism

"employs various techniques that endow all things with a deeper

meaning and reveal mysteries that always threaten the secure

tranquility of simple and ingenious things... it is a question

of representing before our eyes, in an intuitive way, the fact, the

interior figure, of the exterior world"

1e.

He spoke of a "gegenstandlichkeit', or a sensitivity to objects.

Many of Roh's comments about Magic Realism stem from his

interest in phenomenology, a philosophical methodology which

studies structures within our consciousness. Roh

commented further about the emergence of Magic Realism "the autonomy of the

objective world around us was once more enjoyed; the wonder of

matter that could crystallize into objects was to be seen anew"

1f.

These comments echo those by De Chirico who wrote

"Every object has two aspects: the common aspect, which is the one

we generally see and which is seen by everyone, and the ghostly

metaphysical aspect which only rare individuals see at moments of

clairvoyance and metaphysical meditation. A work of art must relate

something that does not appear in its visible form"

1g.

In his 1925

book Franz Roh enumerated the stylistic characteristics of Magic

Realist paintings as compared to Expressionism. He envisioned Magic

Realism as a broad movement, one which was also evident outside of

Germany. Roh identified seven sources for Magic Realism. Each of

these sources initiated a distinctive type of art. The multifaceted

origins of Magic Realism have been overlooked by many writers and

critics, many of whom promoted narrowed definitions of the art term.

However, most of these variants fit under Roh's broad umbrella of

Magic Realism.

Roh emphasized that Magic Realism should not bring

back the Naturalism which was prevalent in the last decades of

the 19th Century. Rather than depending on mere mimesis, Roh said that the

new art should always originate in the artist's imagination. In many

cases Magic Realism results from a synthesis, often from the

combined influences of more than one of these types of art. Roh's

sources for Magic Realism

1h were as follow:

-

Neoclassical - roughly Hartlaub's right wing. More apparent in Italian

art, especially Il Novocento Italiano.

-

Socially Critical - the so-called Verism of Grosz, Dix, Schlicter

and others.

-

Metaphysical - art influenced by Metaphysical paintings.

-

Naive - art influenced by Henri Rousseau or by neo-primitivism (Carra).

-

Hardened Expressionism - Beckmann, Carl Hofer, Albert Birkle and

others.

-

Constructivists artists in Germany and France, including Oskar

Schlemmer and the French Purists.

-

Colorists working with a new type of tonal painting, including

Hermann Huber.

The first five groupings proved to be the most important. This overall diversity was not without precedent

in major art

movements. For example, Post-Impressionism refers to broad

divergences from Impressionism in the 1880s and 90s. Both Symbolism and

Surrealism were complex movements, notable for considerable variations in origin,

style and content. The initial multiformity of Magic Realism as seen

in the early 1920s narrowed over time. Several variations evolved

and coalesced into national types, mainly in Italy, the Netherlands

and in the Americas.

The Surrealist movement developed in the 1920s mainly along two

important paths. Initially it was driven by writers in their works

of automatism, arising from the exploration of the subconscious and

free association. In the late 1920s and 1930s veristic surrealism

developed in the visual arts, initially sharing some traits of Magic

Realism. In many early works from the 1920s, particularly

those of Salvador Dali and Rene Magritte, the

characteristics of Magic Realism were quite evident. However by the early 1930s veristic Surrealism

increasingly incorporated fantastic imagery, biomorphism and

irrational elements which distanced it

from Magic Realism.

German artists developed a fascination with a newly found world of

objects during the Weimar period, fueled by

a technological revolution and the emergence of a mass culture. At

the same time, the political and economic instability during the

interwar period fomented alienation of the individual and caused

intense cultural

anxieties. The manifestations of these insecurities was evident in

the

use by artists of visual devices, some of which Giorgio de Chirico referred to as defamiliarization, or making the ordinary seem strange.

Thus came about the development of "The Uncanny", an aesthetic which

became as important to Magic Realism as the sublime had been for

Romanticism in the previous century. The Uncanny was often seen in

representational art produced between 1920 and 1960

1i. It can arise

simply from the isolation of objects within a painting. From the mid

1930s on

it became an important, if not an essential, component of Magic Realism,

although in some cases its presence appears to be subtle, or at least not

readily obvious.

In the late 1920s Magic Realism developed in other European

countries and in the Americas. This was also a time in which Surrealism began to build up steam as an art

movement, and it was to soon overshadow Magic Realism. Andre Breton, as

the foremost organizer of Surrealism, actively recruited both in

Europe and North America. His efforts did not always bear fruit. As

Fridha Kahlo bluntly put it, "I don't paint dreams or

nightmares. I paint my own reality"

1j. In France and Belgium, artists

like Pierre Roy and

Paul Delvaux, both admirers of Giorgio de Chirico, produced

works that bordered on an improbable reality. Important Magic

Realist active during the 1930s included

Balthus in France,

Cagnaccio di San Pietro and Gregorio

Sciltian in Italy,

Edward Wadsworth and

Tristram Hillier in England, as well as

Antonio Berni in Argentina. During the same

period, Dutch artists Carel Willink,

Raoul Hynckes,

Dick Ket, Wim

Schumacker and Pyke Koch

worked in an imaginative type of Realism to establish a strong tradition

of Dutch Magic Realism, one which lives on to our present day. Pyke Koch

provided a concise definition of the mission of the Magic Realist,

"Magic Realism is based on the representation of what is possible,

but not probable"

1k.

a time in which Surrealism began to build up steam as an art

movement, and it was to soon overshadow Magic Realism. Andre Breton, as

the foremost organizer of Surrealism, actively recruited both in

Europe and North America. His efforts did not always bear fruit. As

Fridha Kahlo bluntly put it, "I don't paint dreams or

nightmares. I paint my own reality"

1j. In France and Belgium, artists

like Pierre Roy and

Paul Delvaux, both admirers of Giorgio de Chirico, produced

works that bordered on an improbable reality. Important Magic

Realist active during the 1930s included

Balthus in France,

Cagnaccio di San Pietro and Gregorio

Sciltian in Italy,

Edward Wadsworth and

Tristram Hillier in England, as well as

Antonio Berni in Argentina. During the same

period, Dutch artists Carel Willink,

Raoul Hynckes,

Dick Ket, Wim

Schumacker and Pyke Koch

worked in an imaginative type of Realism to establish a strong tradition

of Dutch Magic Realism, one which lives on to our present day. Pyke Koch

provided a concise definition of the mission of the Magic Realist,

"Magic Realism is based on the representation of what is possible,

but not probable"

1k.

In the 1920s an important development in American art occurred,

which was at first referred to as Cubist Realism, then as the

Immaculate School and eventually as Precisionism. The movement

encompassed a range of styles, from abstraction to an early type of

photorealism, and covered architectural and industrial subject

matter along with the vernacular and provincial. The most prominent

of the Precisionists was Charles Sheeler, who developed a realistic

style in the late 1920s, reminiscent of Neue Sachlichkiet.

Sheeler and several other painters associated with Precisionism were also

among the first Americans to produce Magic Realism.

In the 1920s American artist Grant Wood made

several study trips to Europe. He came away most impressed with the

precision and clarity that he saw in the works of the old Flemish

masters, especially those of Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling. He also

saw firsthand the developments occurring in German

%201930%201b.jpg) contemporary art. Two distinct types of Magic Realism appear in his

work produced after 1930. First his portraits are done in the style

of the Flemish and German masters and include both obvious and

subtle symbolism.

In his landscapes, he often makes use of naive

stylizations and miniaturization.

Though Grant Wood is generally considered to be one of the three

major Regionalist painters, many of his

paintings are wonderful examples of Magic Realism.

contemporary art. Two distinct types of Magic Realism appear in his

work produced after 1930. First his portraits are done in the style

of the Flemish and German masters and include both obvious and

subtle symbolism.

In his landscapes, he often makes use of naive

stylizations and miniaturization.

Though Grant Wood is generally considered to be one of the three

major Regionalist painters, many of his

paintings are wonderful examples of Magic Realism.

During

the 1930s the Great Depression had a signification impact on

American artists. Many struggled to make a living and sought

government support in the WPA Federal Art Project. An indigenous

type of academic art developed in the United States during the

1930s, which is referred to as The American Scene. The subject

matter chosen by many artists during this period was often anecdotal, either involving some aspect of social commentary (Social

Realism) or portraying the regional characteristics of American rural

culture (Regionalism). A wide range of styles developed during this

period, from academic naturalism to naive stylization, and including

an indigenous expressionism. Meanwhile Surrealism was formally

introduced in the U.S. in late 1931 at an exhibition titled "Newer

Super Realism" at the Wadsworth Athenuem in Hartford, CT. Included

were works by De Chirico, Salvador Dali, Max Ernst and Pierre Roy. A

new variation of American art was spawned during the 1930s, called

Social Surrealism, which was a blend of Surrealism with Social

Realism. Paintings by James Guy and Walter Quirt were typical.

Generally American painters were less interested in psychoanalytical

introspection and probing of the subconscious than their European

counterparts, and their interactions with Surrealism were defined by

an American iconography and outlook. In the 1930s many artists

produced works that incorporated fanciful elements, but they did so

within the context of a basically realist framework.

Strange, mysterious or

uncanny elements were often embedded in many paintings, and

narratives were often ambiguous or partially hidden. A new type of American art evolved,

Realism

with overtones of Surrealism. This art became known as

Magic Realism. The painters of the 1930s often cited as producing this

type of art included

Ivan Albright,

Peter Blume,

Ben Shahn, O Louis

Guglielmi and

Philip Evergood.

The late 1930s saw an emigration of European artists to

the Americas, including many connected with the Surrealism movement.

These artists were not always well received by their American

counterparts, and lived mostly in isolation. Most of the Surrealists

settled in New York City, yet when Breton arrived in 1941 he was

unable to remobilize the formal movement. Regardless of cultural

barriers and the fact that it failed to flourish as an American

movement, Surrealism had a rather significant impact on American art

during the 1930's and 40s, providing liberation from conventionalism

and the prevailing attitudes that had previously favored Regionalism.

Surrealism also had a significant influence in the development of Abstract

Expressionism.

the Americas, including many connected with the Surrealism movement.

These artists were not always well received by their American

counterparts, and lived mostly in isolation. Most of the Surrealists

settled in New York City, yet when Breton arrived in 1941 he was

unable to remobilize the formal movement. Regardless of cultural

barriers and the fact that it failed to flourish as an American

movement, Surrealism had a rather significant impact on American art

during the 1930's and 40s, providing liberation from conventionalism

and the prevailing attitudes that had previously favored Regionalism.

Surrealism also had a significant influence in the development of Abstract

Expressionism.

In 1943 an exhibition entitled "American Realists and Magic

Realists"

1l was assembled at the Museum of Modern Art in New York by

Dorothy C. Miller. Many young artists who would help develop Magic

Realism into a mature movement were represented in this exhibition,

including

Jared French,

Paul Cadmus,

Charles Rain and

Andrew Wyeth. Within a few years

George Tooker,

Henry Koerner, Robert Vickery,

John Wilde and Canadian

Alex Colville began to produce paintings

which we now identify with Magic Realism. All of these artists used

Tempera techniques, which dated back to the Early Renaissance. Their

paintings were carefully crafted objects of art, with imagery that was

infused with metaphoric and symbolic elements. Some of the paintings

by these artists featured "surreal" or dream-like nuances. Yet

none of the American Magic Realists were directly connected with the

Surrealist movement. In many ways the developments of Magic Realism

in the 1940s bypassed and surpassed Surrealism in the Americas.

During the 1950s many of the artists associated

with Magic Realism exhibited at the

Edwin Hewitt Gallery in New York City, and the movement had a

significant following..

Although sharing some common ground, the approach of the Magic

Realist differed greatly from that of the Surrealist. In contrast to

methods that encouraged the spontaneity and irrationality of

Surrealism, the Magic Realists carefully planned and meticulously

executed intricate compositions. George Tooker once stated "It is the

novelty and shock value of the surrealists that disturbs me. I am

after painting reality impressed on the mind so hard that it recurs

as a dream; but I am not after painting dreams as such, or fantasy"

1m.

In the late 1940s and early 50s Magic Realism flourished,

distinguishing itself from other movements such as Social Realism

and

Surrealism.

During this period Magic Realism also helped to carry the banner of

Realism, during the heyday of the Abstract Expressionist movement. The art

establishment of the day marginalized representational art.

Only in the late 1960s did the pendulum of tastes began to swing

away from abstract styles. However Photorealism and Hyperrealism,

with a more detached approach to content, became the preferred

approach for a new generation of artists. Fortunately American Magic

Realists have not been forgotten and finally received some overdue recognition in recent

years. Surrealism.

During this period Magic Realism also helped to carry the banner of

Realism, during the heyday of the Abstract Expressionist movement. The art

establishment of the day marginalized representational art.

Only in the late 1960s did the pendulum of tastes began to swing

away from abstract styles. However Photorealism and Hyperrealism,

with a more detached approach to content, became the preferred

approach for a new generation of artists. Fortunately American Magic

Realists have not been forgotten and finally received some overdue recognition in recent

years.

Franz Roh's insights regarding Magic Realism were made during the

first few years of the new movement. Almost 90 years later, we have the advantage of being

able to look backwards and reevaluate Roh's multifaceted groupings. It now seems more

useful to base groupings on

prevalent types and sensibilities, rather than purely on origin. Here is one

possible set of reappraised groupings.

-

Naive -

the naive influence was especially important during the early years,

with roots in primitive and folk art.

-

Architectonic - Industrial landscapes. cityscapes and townscapes

were common themes.

Includes many works by Precisionists painters.

-

Illusionistic - this best describes the usage of various devices

and techniques that were borrowed from historical art to cast contemporary subjects in an

unusual manner. This group includes the roots of the

fantastic art movement, already

recognized by Franz Roh in 1925.

-

Socially Engaged - includes German Verism and some works of

American Social Realism.

-

Enigmatic - includes art influenced by Metaphysical art and art

that contains "The Uncanny".

-

Metaphoric - the importance of personal and contemporary metaphors

is seen in the advanced works by many Magic Realists.

-

Quintessential - The

revival of interest in Renaissance realism by artists in the

four decades following World War I combined with contemporary

themes to develope a new sensibility.

Because

of its broad and somewhat paradoxical nature, it is difficult for

many people to get a grasp of Magic Realism conceptually. Franz Roh

intended it to be an inclusive rather than an exclusive term. While

at times Magic Realism provided an unflinching or raw look at humanity, it

often took a more oblique or evasive point of view. Often cold,

discompassionate and detailed, Magic Realism raised more questions about life

than it provided answers. It attempted to mesmerize rather than

demystify. Regardless of what definition one applies, it is

important to understand that Magic Realism was in fact one of the

major trends of Realism during the first half of the

20th Century. Magic Realism

thus found a significant niche between Straight Realism and

American Scene painting on one side and Surrealism on the other.

Magic Realism was never purely illusionistic, almost always having a

strong psychological component.

Magic Realism describes

a type of art that flourished during the four decades following World War I.

Initially defined by its ultrasharp focus, coldness and other

technical characteristics, its contemporary content distinguished it

from the Realism of the 19th Century. It often contained subtle twists of the quotidian, but in

a broad sense most Magic Realism paintings emerged from a Weltanschauung

(worldview), stemming from the pressures of the massive social events which transformed society in the first half of the 20th Century. Initially seen as

a stylistic reaction to the latter phases of Expressionism, Magic Realism was redefined

by American artists in the 1940s and 50s, often referring to

intricately detailed works of art depicting everyday life as

something familiar but at the same time as something strange or

unnatural.

Magic

Realism differs from many other art movements in that most of the

artists associated with it did not consider themselves part of

an avant garde and preferred to remain clear of the publicity and controversies of

the art establishment. This was a movement of independent artists,

without champions or manifestoes. As a result, the general public as well as many art critics were never quite

clear about what the term actually meant. At the same time,

there is no doubt that a widespread current within figurative

painting occurred during the four decades that followed World War I, a

movement

that is distinguishable from Expressionism, Surrealism

and Social Realism. Magic Realism quietly developed from many

commonalities among artists that included an affinity for the traditions

of techniques, and a love of art history. Magic Realists also shared

a collective awareness of mankind's struggle to adapt to the many

insecurities of the modern world. Most of the major practitioners of

Magic Realism have now passed on, yet they have left us a

magnificent legacy.

public as well as many art critics were never quite

clear about what the term actually meant. At the same time,

there is no doubt that a widespread current within figurative

painting occurred during the four decades that followed World War I, a

movement

that is distinguishable from Expressionism, Surrealism

and Social Realism. Magic Realism quietly developed from many

commonalities among artists that included an affinity for the traditions

of techniques, and a love of art history. Magic Realists also shared

a collective awareness of mankind's struggle to adapt to the many

insecurities of the modern world. Most of the major practitioners of

Magic Realism have now passed on, yet they have left us a

magnificent legacy.

A list of the artists associated with Magic Realism follows below. This

list is not exhaustive. A great many paintings produced after World

War I exhibit the stylistic characteristics enumerated by Franz Roh

in his 1925 book. Although Roh addressed content in less specific

terms, his multifaceted groupings of Magic Realism's origins

provided a framework on which others built a movement. Important Magic Realists are followed by

two asterisks, with other significant artists followed by one

asterisk. Commentary about most of these painters has been provided

within

their

galleries. Annotations and references for this article are

available on request..

"They (Magic Realists) used a form of stylization whereby the

observed phenomenon was reduced to its essence, confirming the

oneness of the gestalt despite the multiplicity of its aspects.

Notwithstanding their avowed goal of capturing the appearance of

momentary phenomenon with the utmost fidelity, their unconscious aim

was to transcend the many contingent modes of reality and create an

eidos, an abstract essential form ; therefore their realism was

never quite "real", but rather a synthesis of their perceptions

expressed in the disciplined, methodical treatment of the painted

image: the experience of vision. This phenomenon is inseparably

associated with appearance as phantasia." Art Historian Edith

Balas, from The early works of Henry Koerner, 1945-1957.

Georg

Kremer - Email:

editor@monograffii.com

|

Images listed in

Descending Order (Click on Image for Enlargement) |

|

The Mountain

(1937) by Balthus |

|

Self Portrait as a

Clown (1921) by Max Beckmann |

|

Stilleben mit Krug

Pflanze und Spielkarten (1925) by Alexander Kanoldt |

|

Triglion (Imperial

Countess Triangi-Taglioni) (1926) by Christian Schad |

|

Die große

Hafenstadt - The Big Port (1928) by Herbert Reyl-Hanisch |

|

Ferruccio Ferrazzi,

Orizia agli specchi 1925 |

|

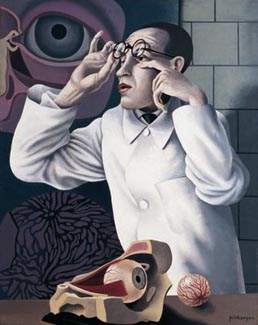

Selfportrait with

ophthalmological equipment (1928-30) by Herbert Ploberger |

|

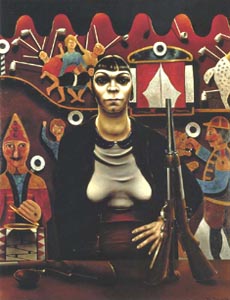

Shooting Gallery

(1931) by Pyke Koch |

|

Arnold Comes of

Age (Portrait of Arnold Pyle) (1930) by Grant Wood |

|

Jukebox (1953) by

George Tooker |

|

Automation (1979)

by James Wyeth |

| |

|

Artists whom have connected to Magic

Realism |

|

| |

|

|

Notes:

1a) page 16 - Magic Realism Rediscovered, 1918-1981,

Seymour Menton, Art Alliance Press, London, c1983.

b)

page 18 - New Objectivity Neue Sachlichkeit - Painting in

Germany in the 1920s, Sergiusz Michalski, Taschen, 2003.

1c)

page 113 -

German Art in the 20th Century.

Franx Roh, Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Society, Ltd,

1958.

1d) page 57 - Magic Realism Rediscovered, 1918-1981,

Seymour Menton, Art Alliance Press, London, c1983.

1e)

page 24 - Magic Realism: Theory,

History, Community, edited by Lois Parkinson Zamora, Wendy B.

Faris, Duke University Press, 199

1f)

page 24 -

Magic Realism: Theory, History,

Community, edited by Lois Parkinson Zamora, Wendy B. Faris,

Duke University Press, 199

1g)

page 182 - Wonder and Exile in the New World, by Alex Nava, Penn

State University Press, 2013.

1h)

page 154

- German Post-Expressionism, Dennis Crockett,

The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999

1i)

Introduction - The Unconcept, The Freudian Uncany in

Late-Twentieth-Century Theory, SUNY Press, 2011.

1j)

Frida Kahlo quoted in Time Magazine, "Mexican Autobiography"

(27 April 1953)

1k)

page 23 - Magic Realism Rediscovered, 1918-1981,

Seymour Menton, Art Alliance Press, London, c1983.

1l

American Realist and Magic Realist, Catalog, MOMA, New

York, Introduction by Lincoln Kirsten, 1943.

1m)

Page 24 - Reality Recurs as A Dream - George Tooker, D.C.

Moore Gallery 2011

Additional

References to be provided upon request.

Recommended Reading: |

|

Magic Realism Rediscovered, 1918-1981,

Seymour Menton, Art Alliance Press, London, c1983.

American Realism,

Edward Lucie-Smith , Thames & Hudson, 2002.

American Realist and

Magic Realist, Catalog, MOMA, New York, Introduction by

Lincoln Kirsten, 1943.

German Art in the 20th Century.

Franx Roh, Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Society, Ltd,

1958.

German Post-Expressionism, Dennis Crockett, The

Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.

Illusions of Reality, Naturalist Paiunting, Photography and Cinema,

1875-1918, Gabriel P. Weisberg, Van Gogh Museum, Ateneum Art

Museum, Mercatorfonds, 2011

Magic

Realism: Defining the Indefinite, Jeffrey Weshsler, Art Journal,

Winter 1981.

Magic Realism: An

American Response to Surrealism (Exhibition Catalog /

June 12-September 6, 1999) - Southern Alleghenies

Museum of Art, Loretto, Pennsylvania.

Magic Realism: Theory,

History, Community, edited by Lois Parkinson Zamora,

Wendy B. Faris, Duke University Press, 1995.

New Objectivity Neue

Sachlichkeit - Painting in Germany in the 1920s, Sergiusz

Michalski, Taschen, 2003.

Realism and Realities. The Other Side of American Painting 1940-1960,

Greta Berman and Jeffrey Wechsler, New Brunswick Rutgers University,

1982.

Realism, Rationalism, Surrealism - Art between the Wars by

Briony Fer, David Batchelor and Paul Wood, Yale University Press

1993, ISBN 0-300-05518-8

Reality Recurs as A

Dream - George Tooker, D.C. Moore Gallery 2011

Surrealism and American Art 1931-1947,

Jeffrey Wechsler, Rutgers University Art Gallery, 1977 (exhibition

catalog)

The

Uncanny, Nicholas Royle, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, New

York, 2003.

The Unconcept, The

Freudian Uncany in Late-Twentieth-Century Theory, SUNY Press,

2011.

Copyright to

The Essense of Magic Realism

registered on January 1, 2015 with the United States Copyright

Office, a Department of the Library of Congress.

|

| |

|

|